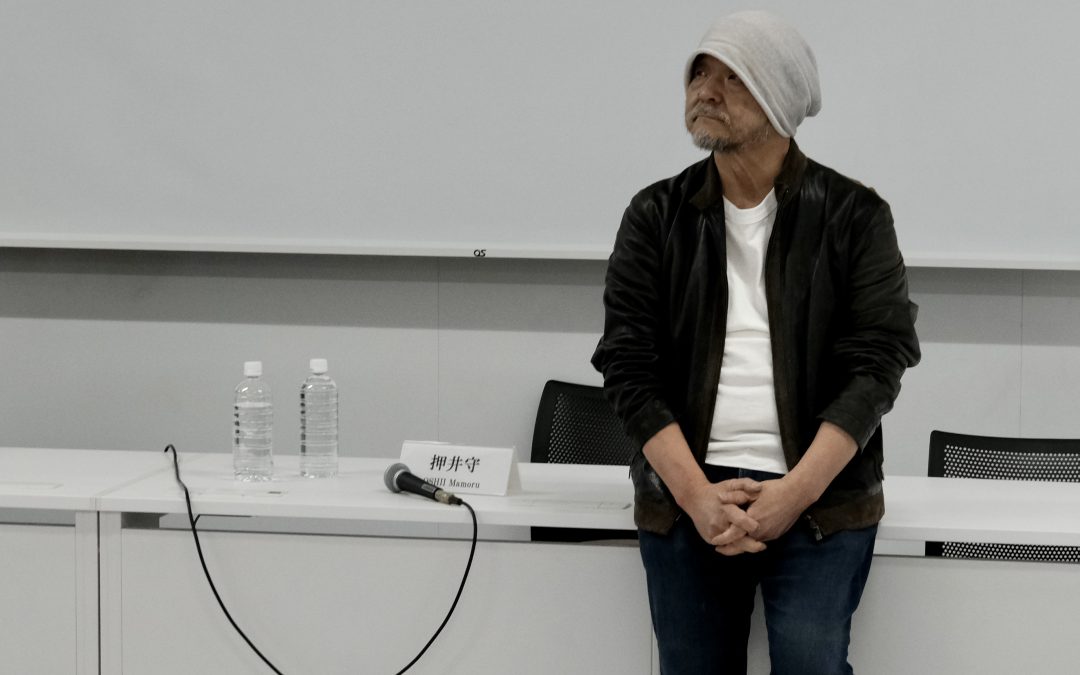

The Niigata International Animation Film Festival held its first edition in March 2023, with a varied program showcasing works from around the world. And to top it off all and start this new festival with style, the head of the festival’s jury was none other than the world-renowned film director Mamoru Oshii.

Mamoru Oshii’s works, such as Patlabor 2 and Gosenzosama Banbanzai, have marked anime history forever, revolutionizing how animes are made and inspiring a new generation of creators.

We had the chance to sit down with Mr. Oshii and discuss his experience as the head judge of the festival, his movie Sky Crawlers, which had a special screening at the festival, and his opinion on the current anime industry. This interview occurred a few moments before the award ceremony, and the atmosphere was heavy.

This article is available in Japanese. 日本語版はこちら

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

Mr. Oshii, as president of the jury, what are your ambitions or hopes for this festival?

Mamoru Oshii: To tell the truth, I don’t like film festivals. The reason for that is that they’re so annoying. Overall, I’ve been to a lot of festivals in Japan and overseas, and I’m always so busy with interviews like this (laughs)… I have to be everywhere, and even though I’ve been to Cannes or Venice, I couldn’t go anywhere, not even walk around town or eat in the good restaurants. It’s always interviews and meetings, so to tell the truth, I can’t even remember where I went except the hotel and the festival’s headquarters.

Of course, I can’t even watch movies, either. In all the festivals I’ve been to, I’ve never seen the movies from other directors that were screened. I’ve only seen Godard’s latest film in Cannes once. So basically, for me, going to a film festival means doing interviews, it’s the same… So it’s pretty exhausting (laughs).

Overall, it’s not much fun, and I never really get the occasion to talk with other directors. It’s not very different in Japanese festivals either. But this time was one of the few times when my schedule made it worth going. I could watch films, meet directors or rather all kinds of industry people. In that sense, I’d say I’m happy about it. Moreover, it’s really close to Tokyo: Niigata is just two hours by train. If you want to know what I’ve been doing with my free time, it’s mostly been reading books at the hotel. I haven’t been around town at all, so I guess that hasn’t changed.

But, to stop just talking about myself, if I had to say what’s the meaning of film festivals, in the end, it’s about business. Even though it’s not the case for this festival. Rather than a testing ground for what will perform well on the market, it’s meant to be an occasion to meet other directors and industry members. Eventually, buyers from all over the world will come, start business talks here and there, and this festival will really be acknowledged as such. That’s what I’d like for this festival: animation works rarely get distributed internationally, so I’d be happy if more occasions for it could happen.

People may be surprised that business plays such a big role, but they shouldn’t be. They think film festivals are festivals above all, right? It’s where film lovers gather together and talk about films… There’s some of that, but if there’s nothing else, the festival won’t happen again: it has to be sustainable in some way. It’s only if there’s a business incentive that good works are presented. You have to get the funds for the guests, and it’s only if you clear that condition that the festival can be good.

However, if you just focus on that, it will end up like Cannes or Montreal: just a marketplace. That’s a bit problematic. You don’t need to go as far as installing corporate booths: in my opinion, the best would just be people meeting in the lounge or lobby of the hotel where everybody is, starting business talks that they can resume later in Tokyo. That’s the function film festivals serve for society: they’re basically business events. But at the same time, it’s the occasion to see a lot of works you couldn’t see elsewhere. Things like masterclasses or talk shows are very important as well. This festival still has a ways to go in terms of business, but there were plenty of opportunities to see films from all over the world and exchange with all kinds of people: there wasn’t just me, but also Katsuhiro Otomo, Rintarô… Outside of the lectures, I’ve also had the occasion to meet lots of young people, so I’m very happy about it.

In a recent interview, you said that the Japanese industry is “stagnating” and that there’s no passion. Could you explain what you meant?

Mamoru Oshii: There are multiple reasons for that. Basically, I think that Japanese animation is definitely stagnating right now. At first glance, all works look the same, especially for people who don’t watch a lot of animation. If you don’t pay close attention, there’s no difference, the characters, the way to use colors, it’s all identical… But actually, in animation, there are as many styles as there are works. Even if Japan may be better at a certain style, there should always be a certain degree of stylization in the designs that perfectly fits each individual work. But since, in actuality, the characters come first and people only think about the story afterward, the order is reversed, and in the end, everything ends up looking the same. I think that’s the biggest reason for stagnation.

Before saying that there’s no passion in the industry or that the young people aren’t passionate anymore, there’s the fact that viewers’ tastes have become too narrow: they just like these, what’s it called, these moe-style characters. If the market is like this, it’s because of the viewer’s tastes. That’s the biggest reason.

Now, if you ask me the reason for this, it’s that animation works don’t circulate enough. In an economic sense, I mean: the subcultures that surround the works, or rather than “subculture,” maybe the “peripheral” culture, things like toys, merchandise, and goods, including cosplay, all this constitutes the totality of a work. In a situation like this, things that are easy to sell are going to be favored. But if you take the foreign works that were screened here, what goods could be made out of it? Nothing. Since the time I started my career, animation and all visual media haven’t been estimated as works of art but have become essentially a commercial activity. And when the commercial aspect comes first, designs are going to change, and tastes are going to become more restricted to favor what’s easy to sell.

In these conditions, mass production becomes easier as well. Animators work on multiple things at the same time, so it’s easier for them when the style doesn’t radically change each time. The end result of all this is that all works start looking alike.

Nowadays, the overwhelming majority of animation being produced is adapted from whatever manga or light novel is popular: that must be around 80% of what’s being made. There are almost no original productions anymore. For this festival, the Japanese works were original, but that’s the exception: there’s almost nothing that comes from the studios themselves, and because of this, the industry as a whole is stagnating. And once you get into that cycle, it’s difficult to get out. You can’t say that studios come first anymore. Directors don’t have that much freedom, especially the young ones.

The older ones, the generation above me, are all in their 70s or 80s and have stopped working; they’re all retired. These people did all kinds of things; you could even say that they’ve done it all. That’s probably because creators felt like they could do something different each time. The people supporting the industry today have witnessed this. The thing is, people who have grown up watching animation can only copy. In my generation, we didn’t watch what our elders had made, and we had to think up everything by ourselves. I think it’s also an important factor: it’s not just about commercialism or its effects; there are also some structural factors.

However, I think things are going to change. The young people who watch today’s animation may end up doing the same thing once they enter the industry, but in the end, each generation reacts to things in a new, unpredictable way. After the current era of stagnation, I hope that we may witness the arrival of a more chaotic generation. But well, what do I know? I can’t tell if I’ll still be there when that happens.

In any case, at this festival, there are all kinds of different styles among the foreign works. You don’t always have the occasion to see such things, and I found that very stimulating. For instance, now you can do films with game engines and create a new style and working method. People working in video games are aware of that, of course, but depending on what engine you use, the style changes as well, both the designs and the overall atmosphere. For example, if you go with the most orthodox one, the Unreal Engine, the game will more-or-less tend toward the mainstream. For game creators, the engine really is the most important technology. And out of something so interesting, it’s possible to make not just games but also movies. Recently, big-budget games have started imitating movies, and they’re basically the same as cinema now. Or, to put it even more bluntly, they’re doing something even better, against which we directors can’t even compete. Of course, that’s also because the budgets are too different.

To give you examples, I’m thinking about something like what director Hideo Kojima’s been doing, things like Metal Gear or Death Stranding: this is cinema. While you play the game, half of the experience is watching a film he created. It’s incredibly well-made, and we can’t do something like it because he’s got this engine. Because of that, it’s possible to make films by using a game engine – you can even make features with very few people. I think it’s definitely going to become a big trend, a new movement. That’s because animators and directors today all play video games, so they know about this, and games’ influence on animation may grow bigger and bigger.

But they can’t do exactly the same thing: the budgets and scale aren’t the same, and the market isn’t the same. Video games are international; they’re selling millions of units all over the world. In comparison, Japanese media – animation, TV, cinema – is much, much smaller. So they can’t do the same thing. But in terms of awareness, of impressions, since creators witness these things, I think games have the power to create big changes.

Another thing is shorts, things like game PVs. Nowadays, there are a lot of short films with a strong narrative, where it’s not just about showing cool images with the music. This has a lot of influence on young artists. There are a lot of ways to express reality in animation: not just features, but all kinds of formats around it: video games, commercials, music videos, short clips, and a lot of new things can emerge on these boundaries.

I also think there’s more demand for things like that as well. A big question for this festival’s competition was how to evaluate such works: is it alright to call it cinema? If not, what is it? How can we judge and evaluate them? What kind of prize should we give them? Some works have no chance of getting an award with the usual criteria, so it’s necessary to change those criteria because the way they were made is different. Works made for children, completely artistic works, very dark things made for adults, they’re all made differently. So in the end, it’s not about which is best, or which should win first place, second place… We have to change the way we judge things. That’s what I insisted on the most during the awards selection.

It’s necessary to ask these questions because there’s no method of evaluation that everyone can agree on. What and who do we award? It’s impossible to answer this with the way of thinking we have had until now. Of course, there has to be a Grand Prix because it’s the symbol of any film festival, but the question is what to do with the other works. When I tried it out, what I had to do became very clear. But that only applies to foreign works: Japanese works are basically all the same, dramatic stories adapted from a manga. In the end, it was an interesting experience, and I’m glad I had the opportunity to confirm all this also because such great works were presented.

At first, I didn’t want to do it, you know, because I hate having to judge things. I’ve been on the other side, so I hate having to do it. But this time, I was spared this feeling because there were so many great works that made me glad to be here and stimulated me in so many ways.

Outside of the competition, what left the strongest impression on you?

Mamoru Oshii: It had to be the screening of one of my earlier works, Sky Crawlers. Many people came, but to my surprise, more than half hadn’t ever seen it before. Most of them were young, but it made me happy to see that there are still people who have yet to see it. Watching films together on a big screen, you don’t often get that chance once a film’s initial run is over. Actually, it’s not that rare for my films, and I’m always thankful for it because watching films together and watching something on your own on a streaming platform are totally different experiences. On a big screen, you can feel that the film is still alive. My Sky Crawlers is still alive as well.

Rewatching it, Sky Crawlers really felt like a French New Wave film…

Mamoru Oshii: (Laughs) Well, about that, the truth is that I wanted to do something like Wim Wenders’ Paris, Texas. I wanted to see whether it was possible to do something similar in animation, particularly the flow of time and the ability to express time itself. That’s all there is to it.

Is that so?

Mamoru Oshii: Basically, I wanted something that felt like a live-action film and with the kind of characters that you can’t find in animation: they look like children, but inside, they’re children… All this kind of difficult stuff. I tried out a lot of things. But really, thinking about it, what makes me the happiest is that, even though it’s a pretty old work, it was shown on a big screen, and all kinds of people could see it. Also, the masterclass I held with those young students. That was fun. They all looked like they were having fun, but they were also very serious, perhaps too much… You were there, weren’t you?

We were.

Mamoru Oshii: I wish it could have been a bit more fun, I wanted to make lots of jokes and everything, but they all looked so serious. That’s how young Japanese are today, I guess.

I only realized now that young people today they’re honest when they’re on their own, but as soon as they’re in a group, they get on their guard. But it was such a rare occasion; they should have asked about more things. If not, nothing happens, does it? This happens wherever I go. This time I talked for a long time, around two hours, and this doesn’t happen every day, so even if it was tiring, it was quite interesting.

After Sky Crawlers, you stopped doing animation for some time. Was there any particular reason?

Mamoru Oshii: Well, after Sky Crawlers, I did three films, but live-action ones. It’s not like I stopped doing animation or anything, these movies just happened to be live-action, and I put animation on hold for some time. So I didn’t stop working or anything like that: if anything, it was a rather busy period.

First, I did a live-action series, then an SF film in Canada, and finally, I went back to Japan to do a film about high-school girls. I just ended up making these three live-action works in a row, and since this is over, I’ve been back in animation. I’m working in both fields like that; there’s no real order of priority (laughs). Also, animation takes a lot of time: sometimes three years, sometimes even five. So it’s hard to connect projects. What I’m doing right now won’t come out for at least three years. But that doesn’t mean I’m done; it actually means I’m working hard. Everybody is.

The 2023 Niigata International Animation Film Festival organisers, jury members, and award winners.

As it was announced by the organizers and repeated by Mamoru Oshii during the ceremony, the president of the jury insisted on giving a speech and answering journalists’ questions about the price attributions after the ceremony. It happened in a corner of the Ryutopia theater, near the exit, in an uncomfortable way for everyone.

As he told us two days before, Mr. Oshii had a favorite movie and was confident in convincing the other jury members to choose it without turmoil. This movie was obviously Khamsa, the well of oblivion. Jinko Gotoh and David Jesteadt, the jury members, opposed this choice. Khamsa was finally given the Kabuku award, invented and given to Khamsa director Vynom by Mr. Oshii. Vynom stated on stage that his main influence for his movie was Mamoru Oshii’s Angel’s Egg.

Following is Oshii Mamoru’s post-ceremony speech.

During the ceremony, you said you chose work based on the quality of their “expressions.” Could you explain the choice of Blind Willow, Sleeping Woman in regard to that?

Mamoru Oshii: I was curious to see whether they’d find ways to show things that aren’t in Haruki Murakami’s original novel. You probably can’t do it in live-action. From the point the frog appears, it’s impossible. It’s also no good if you think of what today’s animation is like: there’s this pathetic, unpleasant feeling of time going by… So I think we were all very surprised when we saw these extremely ugly drawings. They’re really powerful. Basically, I thought it was almost impossible to make visual adaptations of modern literature, but they used the smallest amount of lines possible and made the movement feel disgusting, which is a really convincing choice. So it’s not about whether it’s a beautiful film or not, because beauty was probably not considered when making it. Actually, it’s a kind of expression that the Japanese couldn’t do. When adapting something, you can’t show everything. So it might be possible to adapt so-called classics in live-action, but I think animation is best suited for contemporary literature. That’s why it got the Grand Prix: the way it expressed things, the things it wanted to say, and the theme were a perfect fit. In fact, rather than just my opinion, it was the only work the three jury members agreed on, so in the end it got the Grand Prix.

In fact, in the pamphlet, the director said that he wanted to achieve things that can only be done in animation, which includes imitating live-action. Would you say it succeeded?

Mamoru Oshii: I would. Each one of the works presented had its own style, but the truth is that in animation, form or style is the very core of a work. But it’s very rare to see something where everything, the message, the art, the way the characters feel, the movement, all match each other. It’s particularly the case in Japan, where everything is made from the same template. The base material changes every time, and the story changes every time, the genre changes, but visually it’s all the same. But from now on, each animation production should have its own unique, individual style. It’s actually the standard way of seeing things in overseas animation, but this is completely ignored in Japan. An interesting result of this festival was making us aware of this gap, of the fact that Japanese animation has become a special “genre” within animation.

The way you chose the prize was rather interesting since you didn’t go with the usual “scriptwriter” or “director” awards.

Mamoru Oshii: Such awards are mostly given out of habit. Whatever the film festival, you’ll find a director’s award, a writer’s award, a music award, and an art award. But in animation’s case, it’s not a good way to evaluate things. As I just said, animation’s true nature is the ability to express things in a variety of different styles, so you can’t just lay out multiple works on a table, compare them and say which one is superior and which one is inferior. It took some time for the jury to realize this (laughs). But thankfully, we all reached an agreement and decided to ditch the usual awarding process and create our own prizes. There were only three this time, but the idea is that prizes should be adapted to what is presented: whereas film festivals up to that point have been doing the absurd job of trying to fit movies in pre-existing categories, we’ve decided to do the opposite and completely renew the process. Maybe it’s why the choice of the Grand Prix was so surprising, but that’s how it should be. It’s not a beautiful film, but it’s incredibly rough and raw and has this subtly obscene mood, which is exactly what Haruki Murakami’s novels are all about. It was conveyed in a wonderful way. So in that sense, I’d say it’s a groundbreaking work.

You could say the awards are what makes a festival special. And it feels like this first edition was very special. How do you feel about this?

Mamoru Oshii: Once we, the jury members, were done with the awarding process, we really felt refreshed. At least we weren’t uncertain about what we had done. Usually, the work of the jury consists of cramming films into categories, so it always feels frustrating, but this time it wasn’t the case. We felt like we would be surprising everyone.

This festival should happen every year from now, right? Do you intend to continue taking part in it? Would you have any proposals for the next editions?

Mamoru Oshii: There still are a lot of things to consider. This time was really focused on the works, but there’s an entire culture surrounding animation, made up of dôjinshi, cosplay, and so on… This peripheral culture is what makes up animation. It’s also becoming a worldwide phenomenon. So the next question is what we do with it. If works are the backbone, the seeds, the parts that bear flowers and fruits are this culture. The way we integrate it will have a major effect on the atmosphere of the festival and its ability to attract visitors. It would be easier to attract people from outside Niigata, although that’s easier said than done. In any case, it’s a major issue for the future. Also, I’d like to increase the number of Japanese works presented a bit. But for that, we need the cooperation of each producer and studio, so we need to think about how to attract them properly.

Among the presented films that didn’t earn a prize, was there one you’d give a special mention to?

Mamoru Oshii: The Three Wreckers Tetralogy was quite punk. It was overwhelmingly powerful, but in the end, it was just grotesque and dark. It’s normal that it’s divisive, but it’s the kind of work you want to show to your children and grandchildren. You can really feel that animation has no limits. That’s I think our “boundary” award is rather revolutionary: you can’t include works like that, which cross so many limits, with the usual awards. The number of works like this should increase in the future, and there’s no difference for viewers because it’s all animation. So I believe that if you want to grasp what animation is as a whole, it’s no longer possible to just look at it from the perspective of narrative feature films.

There was quite a lot of variety in the competition, but the only films from Asia were Japanese. This isn’t very balanced for an international festival, is it? What do you think about this?

Mamoru Oshii: It’s not like we’re the Olympics, where every country has to be represented… So, in the end, a line of quality has to be drawn, and unfortunately, within this limit, there’s mostly Europe, some American works, and then Japan. But this time, we also had a film from Ireland. The Algerian film was special, and it felt very fresh and surprising. So I believe we had quite a varied lineup compared to other art shorts festivals.

Interview by Matteo Watzky and Ludovic Joyet.

Transcription by Comrade Karin. Translation by Matteo Watzky.

We wish to thank Mr. Mamoru Oshii for his time, as well as all organisers of Niigata International Animation Film Festival for their assistance and granting us this opportunity, especially Ms. Akita.

Like our content? Feel free to support us on Ko-Fi!

You might also be interested in

The resurrection of Science Fiction: Mars Express – Long Interview with Jérémy Perin

First with the Music Video Fantasy for DyE and then with Truckers Delight for Flairs, Jérémie Périn quickly made a name for himself and climbed to the top of the animation industry without compromising by working on commissioned films or in the shadow of a mentor....

“A place where only the drawings exist” – Interview with Benoît Chieux

When we first met with Benoît Chieux at the Forum des Images and saw his feature Sirocco and the Kingdom of the Winds, we were extremely eager to hear more. Indeed, not only is Sirocco an impressive animated movie that combines many influences from all over the...

Do anime events have room for creators? – Interview with Koji Takeuchi

The Annecy International Animation Film Festival is a place of many little pleasures, and one of them is to meet with Kouji Takeuchi, a pillar of the anime industry, and learn a little bit more of Studio Telecom's lore, which you can read more about in our previous...

Trackbacks/Pingbacks